Miah, A. (2009) 2029. In: Stubbs, M. & Newman, K. We are the Real-Time Experiment. Liverpool University Press.

Past

In the summer of 2006, I moved from Glasgow to a flat in Toxteth, Liverpool, which did not have internet access. At the time, social media was quickly becoming a popularised practice, I was blogging regularly and FACT’s wireless internet access was free. It still is. As a result, my time in Liverpool began as a client of FACT, one of its many nomadic notebook bearing café goers. We sit in the corner, by the window - ideally with a plug socket in reach – looking out into the atrium. This seems as good a starting point as any to explain part of what FACT means to its community or to those who pass through Liverpool. It also explains why FACT is necessary and what it might accomplish in the future, which is what I want to consider in this concluding chapter.

Even in 2009, after half a decade of free public wireless capability, the United Kingdom, along with many other developed countries, still expects to charge the public for internet access. Yet, free wireless internet access should be regarded as a public good in the 21st century, a public space even, like a park or a bridleway. Internet access is something we should be able to take for granted and expect everywhere we go, without having to pay a fee. Indeed, over the last five years, cities around the world have begun to treat wireless Internet access in this way, free to all, but in the UK the realization of this notion remains elusive.

In London, Mayor Boris Johnson expressed that London should have wifi throughout the city by the 2012 Olympic Games. These are valuable sentiments, but the crucial word – free – is not particularly evident in the campaign. Even the sole restaurant to have free wireless at Euston station has now been swept into another fee-paying ISP circuit. Moreover, Internet dongles are now appearing in the high street, each one charging us far too much for far too little. The aspirations of digital culture have yet to be met, yet so much more could be freely available already. Audio should be free. Video should be free. FACT understands this and its café goers are loyal because of its persistence to deliver open access.

Being vigilant of new media culture – advocating its promise and berating its limitations – infiltrates FACT’s work. Indeed, my three years in Liverpool has shown me that these dual discourses of promise and scepticism pervade many spheres of work in the city. I think this is why the history of FACT is such a contested space. FACT is clearly an organization that arose from collaboration, sharing and opportunism on behalf of upcoming cultural leaders in the city at the time. In 2008, the Chair of the European Capital of Culture, Phil Redmond, described the year as something like a scouse wedding, an analogy that pervaded the year’s media. He described how the process begun with disagreements over how best to deliver an exciting cultural programme, but when the time came, everyone had a good time and it all went very well. This analogy might work for explaining queries into FACT’s origins – whether it was indeed a ‘Liverpool invention’, as Lewis Biggs interrogates here. Biggs’ ‘regionalism’ narrative of FACT’s birth, which demonstrated how it took place amidst considerable political unrest within the UK, reveals even further how FACT might best be thought of as a Liverpool art work, rather than an invention.

Liverpool’s port city and slavery heritage, along with its contemporary ghettoization requires its institutions to make community a central part of their work, which also explains how the birth of FACT fits here. These are endearing qualities of the city and they shape my own experience of it, living now in the 1960s bohemian district, sandwiched between the Asian, African and Chinese communities, with the two cathedrals, a synagogue and a mosque all a short sprint away.

Reading Laura Sillars’ prologue to FACT’s history, I was struck by thoughts about the immediate past, Liverpool’s Year as European Capital of Culture in 2008, which was my major reason for coming to the city. The questions Laura asks might also be asked of 2008, a year with its fair share of challenges. How has FACT’s past contributed to Liverpool’s contemporary art and cultural environment? During 2008, FACT consolidated its past by entering into the Liverpool Arts Regeneration Consortium (LARC) collaboration, itself a product of necessity in times of difficulty leading up to 2008. As one of the major eight cultural institutions in the city, FACT inevitably became – for some – more of an institution than a grass roots organization, though with the arrival of its newly appointed CEO Mike Stubbs it remains artist-led. As such, 2008 consolidated FACT’s role as a key venue for major cultural events in the city, as well as becoming an organization that could just as easily have the Secretary of State for Culture wandering around its atrium, as it might have the prizewinner of ARS Electronica. This speaks volumes about how FACT has adapted over 20 years, defining its trajectory, while also stopping at each juncture to consider its choices.

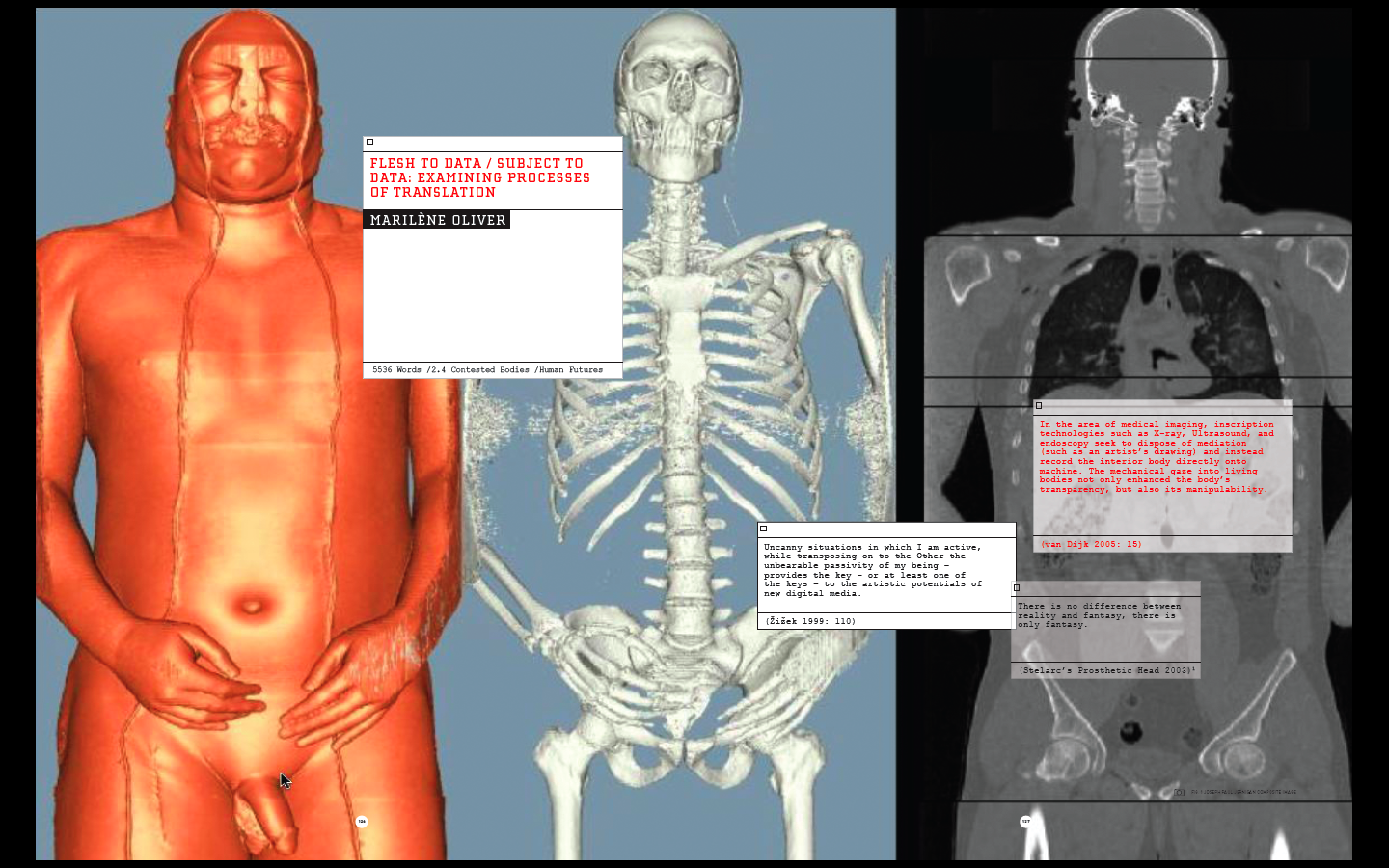

For any successful organization, a rise in status implies a danger of losing the intimate connection with core membership, due to the imposition of other obligations that emerge from major funding opportunities. Concern about such prospective loss, but more broadly of the change that surrounded Liverpool during 2008 seemed integral to all of FACT’s works throughout the year. In 2008, I was fortunate enough to be part of FACT’s conversations on its future. I recall one of the first artists’ workshops of the Human Futures programme, which brought such artists as Stelarc and Orlan together, though not just to talk about bioethics and bioart (see Hauser 2008). Instead, a significant part of our debates focused more on what arts organizations – and artists – should be doing at the beginning of the 21st century.

Present

In 2009, the labour of these discussions bore fruit in the form of Climate for Change, FACT’s first exhibition for its UNsustainable year. Inviting local communities into the gallery space, FACT placed its creative vision in their hands, opening up a dialogue about its future and providing a space where the concerns of its peers could be heard. As an exhibition, its major art works were thus the people who inhabited the space, which brought new communities together and welcomed new publics into their fold. Yet, this was not just an exercise of public engagement or outreach. Rather, the exhibition’s thematic focus on ‘economics and sustainability’ issues, as Mike Stubbs explains in this volume, also demonstrates FACT’s desire to interrogate the conditions of contemporary mediatized and politicized debates about climate change, by linking them with broader issues of social and political unsustainability.

Throughout Climate for Change, I wondered what would be next for FACT. After all, what more can an arts organization do to support local communities than to hand over the gallery space for a period? Perhaps handing over the space permanently would be a more powerful gesture, but FACT’s communities are numerous, their audiences multiple – cinema goers, art lovers, café visitors, book shop browsers, bar quiz buffs, conference delegates, and so on (and even within each of these categories there is substantial variance). This composite audience is not unique to FACT. Actually, it may describe the conditions of being a 21st century arts and cultural institution, the kind of multi purpose media space that is arising in such places as King’s Place London, which opened in 2008. This is not to say that art is merely one of the things that FACT does. Rather, art – along with the two senses of creative technology mentioned by Sean Cubitt in this volume – pervades each of these other works. This is beautifully demonstrated in another 2009 work by Bernie Lubell whose bicycle powered cinema also takes FACT towards its next major intervention, a festival of new cinema and digital culture called Abandon Normal Devices or AND with aspirations of Olympic proportions.

Like FACT’s birth, AND is also the product of collaboration in the arts and new media sector, driven by FACT in Liverpool, Folly in Lancaster, and Cornerhouse in Manchester. Moreover, it arises partly from funds related to the Legacy Trust’s UK investiment in ‘We Play’, England’s Northwest cultural legacy programme for the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games. The producers of the festival are working to ensure the investment extends well beyond 2012, hoping AND to become a key item in the national calendar. Here again, we see the duality of FACT’s identity at work – new cinema and digital culture – as an organization that champion’s new work and invites local communities to scrutinize it, as it does with its long-standing online community broadcast platform Tenantspin.

Abandon Normal Devices also lends itself to multiple, rich interpretations. It is an inquiry into the consequences of normalising processes - both physical and social – while also functioning as a conjunction, inviting the participant to invent associations: Body AND Economy, Art AND Health, Sport AND Culture. This cross fertilization of ideas offers a much needed opportunity to critically interrogate the Olympic period within the United Kingdom, as London 2012 prepares to host the Games for the third time (the first Modern Games city to have had this opportunity). After all, the idea of normality and our critique of it is implicit to the Olympic philosophy, which pivots on notions of individualism, nationhood, excellence and perfection. Indeed, this is prominent when observing how an athlete’s physique is being altered by technology, especially within disability sport. Very soon, it is likely that prosthetic devices will overtake the capabilities of their biological counterparts, thus transforming what it means to be the fastest or strongest person in the world (Miah, 2008, Wolbring 2008).[i] Indeed, in 2012 we might even see the first 100m sprint of the Olympics won by an athlete with prosthetic legs, signalling the beginning of the end of able-bodiedness as a privileged condition.[ii]

The Olympic Movement is also wrestling with its future, as citizen journalists threaten the financial base of the Games by syndicating Olympic intellectual property and as the youth of the world – the Olympic Movement’s core community – shift their attention to video games and alternative sports, which have quite different values to their traditional counterparts. Already, there are major competitions around digital gaming with the first professional gamer, Fatal1ty, occupying central state. Cybersports are a part of this and many of the largest sports relying on digital technologies to constitute the training environment, taking sports into the digital arena.

As the first regionally devolved Olympics, FACT can have a major role in constituting the terms of this period, certainly in the Northwest, but perhaps more importantly by bringing together a national convergence of arts and new media with research into body economies (biotechnology, synthetic biology, AI, energy, etc). These processes have far reaching implications and might even signal the need to abandon traditional sports practices and re-interpret the Olympics once again. Artists can help here and their design of new technological encounters is demonstrative of this. Indeed, it is constitutive of the Olympic enterprise, which has always pushed the boundaries of technological excellence, from taking an Olympic torch underwater at the Sydney 2000 Games to using slow-motion for the first time in broadcasting.

Future

FACT’s birth coincided with that of the Internet, which Tim Berners-Lee conceived on 12 November 1990. One might even say that FACT’s birth occurred at the moment of the Internet’s conception. As the Internet reached maturity around the mid 2000s, the Web 2.0 era transformed the web into a prolific offspring machine, with new nodes arising daily and data-based societies emerging where content production and creativity reached pandemic levels. The next 20 years of both FACT and the Internet will be very different from their first, but it is clear that they will be intimately connected. We already see a glimpse of their promise in Mike Stubbs’ appeal in this volume to establish the Collective Intelligence Agency (CIA), which urges us towards better-networked intelligence, rather than just better-networked stupidity. Information now moves in different ways, both offline and online. Google is beginning to look like an outdated model of information distribution, as new modes of semantic or real-time searching arise through such platforms as Twitter Search.

The implications of this are profound and require organizations to understand that they are no longer the sole proprietors of their Intellectual Property, which includes their public relations and marketing. Consider the fake twitter hashtag that was used around the South by South West (SXSW) festival in 2009, created by people who did not have access to the festival. The prominence[iii] of this ambush media allowed the fringe community to create their own alternative experience. Unlike urls, nobody owns hashtags and, by implication, nobody can restrict their use (yet). Coming to terms with the reality of distributed IP will be a central part of allowing an organization to move from a Microsoft model to an Open Source model. The rise of web 2.0 platforms such as Facebook and Flickr demonstrate this, as communities take ownership of their institutions.

Understanding how best to deal with these challenges requires re-stating what FACT does. Roger McKinlay reminds us that FACT is not driven by technology, but the desire to make technology ‘invisible.’ It is an organization that endeavours to put people together and provide them with the means to realize the potential of new technologies. Such work also involves subverting the parameters of new technology, as demonstrated by Hans-Christoph Steiner’s iPod hacking session, which took place during his recent FACT residency as part of Climate for Change. These aspirations to democratize technology speak to both enduring and emerging dimensions of our posthuman future. Around the world today research programmes are exploring the link between biology and computing, which also describes the intersection of new media art and bioart, a key focus of FACT’s recent work. The prospect of artificial general intelligence (AGI) and the singularity have pervaded philosophical inquiries into cognition and neuroscience over the last decade.[iv]

It is, thus, highly appropriate that we consider, finally, what FACT might be doing precisely 20 years from now in the year 2029. According to Wikipedia – yes, it is also an encyclopaedia for the future – this will be the year when machine intelligence passes the Turing Test and will have reached the equivalent of one human brain.[v] What we cannot know yet is how this will come about. How much of this achievement will be brought about by collaboration between artists and scientists within mixed media laboratories such as FACT?

Our consideration of FACT’s future must be also take into account Liverpool’s future. What will Liverpool look like in 2029? As Roger McKinlay reminds us in this volume, FACT’s first 20 years began during a recession. FACT’s next 20yrs begins in similar times and it is notable that, as Liverpool’s renaissance takes shape and it finds a way of emerging from 20 years of economic neglect, the largest global recession of the last 90 years hits the world. Nevertheless, Liverpool is a much more competitive place now for the visual arts. With new arts and cultural centres such as the Novas Contemporary Urban Centre, A-Foundation, an expanded Bluecoat centre and ever growing independent galleries, the Liverpool’s artistic renaissance is clearly underway.

Despite its name, the truth about what FACT was, is or will become remains elusive. It is still an artist led organization, but its art is not absent of responsibility, since it is also an institution that needs to have concern for such things as accessibility. There are additional opportunities that arise from this. FACT is beginning to play a more central role in shaping governmental policy, particular on digital culture and, in the future, this will surely be a stronger component of its work. It is also building a research capacity and a growing empirical base to align with this role. In so doing, it is also establishing a research Atelier – not a laboratory – proposing new models of undertaking practice based research and complementing this with more traditional forms. This work will help to reset the boundaries of research in the 21st century, back towards a stronger emphasis on arts-based knowledge. As a city, Liverpool is also well placed to support this process, having built legacy research into its year as European Capital of Culture – the first of any city to ring fence such funds around this programme. [vi] Indeed, it is perhaps one of the best-placed city within the UK and possibly Europe to build a model for cultural regeneration and it is apparent that London has similar aspirations for evaluating the impact of the London 2012 period.

From my position as a FACT Fellow, I occupy a space somewhere between the organization and my starting point in Liverpool, as its client. To this end, I perceive a tremendous self-induced pressure on FACT’s programme team to achieve broad, dramatic societal and creative impact through its work, expectations that are praiseworthy and highly ambitious. Yet, if they get even 80% towards those goals, they will have exceeded themselves. As such, I conclude with a pitch for what I would like to see next: a curatorial team established for an exhibition in 2029 or, better yet, 2049. I wonder if that has been done before.

References

Editorial. "Latest Twitter + Sxsw Trend #Fakesxsw." LA Times 2009, http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/technology/2009/03/latest-twitte-1.html.

Hauser, J., Ed. (2008). Sk-interfaces. Liverpool, Liverpool University Press.

Janicaud, D. (2005). On the Human Condition. London and New York, Routledge.

Kurzweil, R. (2005). The Singularity is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology. New York, Viking Press.

Miah, A. (2005). "Genetics, cyberspace and bioethics: why not a public engagement with ethics?" Public Understanding of Science 14(4): 409-421.

Miah, A., Ed. (2008). Human Futures: Art in an Age of Uncertainty. Liverpool, Liverpool University Press.

Miah, A. (2008). Posthumanism: A Crtical History. Medical Enhancements and Posthumanity. R. Chadwick and B. Gordijn, Springer. 71-94.

Wolbring, G. (2008). One World, One Olympics: Governing Human Ability, Ableism and Disablism in an Era of Bodily Enhancements. Human Futures: Art in an Age of Uncertainty. A. Miah. Liverpool, Liverpool University Press: 114-125.

Zylinska, J. (2009) Bioethics in the Age of New Media. MIT Press.

[i] For example, consider the trajectory of Aimee Mullins, whose presence in fashion, film and sport has become iconic of the new enabled paralympian.

[ii] This was a possibility leading up to Beijing 2008, when Oscar Pistorius fought for his legal entitlement to compete. He has already appeared in other competitions, alongside so called able-bodied athletes. It is likely that his trajectory towards the London Olympics will be even stronger.

[iii] For example, the hashtag attracted such established media as the LA Times (2009) to report on it.

[iv] There is also more we might say about the relationship between biology and computing as prominent, competing discourses. As Dominique Janicaud (2005) explains, the bioethical has overtaken the digital as a public discourse, though so much of bioethics relies on digital configurations that it might be reasonable to subsume new media ethics within bioethics, as some authors have begun to explore (Miah, 2005; Zylinska 2009).

[v] This is based on Ray Kurzweil (2005) prediction, which derives partly from Moore’s Law.

[vi] There is, of course, the Liverpool City Council and Arts and Humanities Research Council research programme Impacts08, which draws on many local research collaborations. However, this evidence base also encompasses a range of additional research that has informed the city during these years, such as the City in Film project at Liverpool University and any number of community research projects that FACT and other organizations have implemented.