Make it stand out

What’s been happening?

Congress of Brilliant Minds

Creative Futures: The Rise of Biocultural Capital

![Everything Everywhere: An Academic's Life on Social Media [VIDEO]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/563face7e4b06c325c739ba9/1447019580286-DITKBKRWZ7J8ZG15HCL0/image-asset.png)

Everything Everywhere: An Academic's Life on Social Media [VIDEO]

![The Olympics: The Basics [Russian edition]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/563face7e4b06c325c739ba9/1447019579986-DITAF1GDLXI9VYX6A6V1/image-asset.jpeg)

The Olympics: The Basics [Russian edition]

Creative Futures Institute - year of 2012

![Doping & Cycling: Scrutinising the most superhuman sport [VIDEO]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/563face7e4b06c325c739ba9/1447019579383-EYUHAWVC4BZHDCJOTIKZ/image-asset.png)

Doping & Cycling: Scrutinising the most superhuman sport [VIDEO]

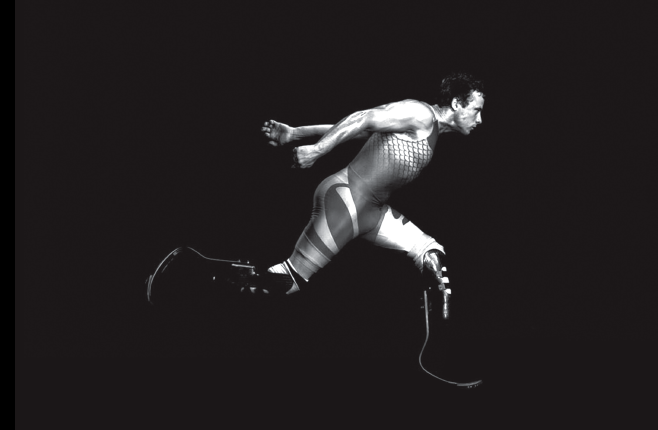

Human Enhancement Technologies: Pushing the Boundaries (2013)

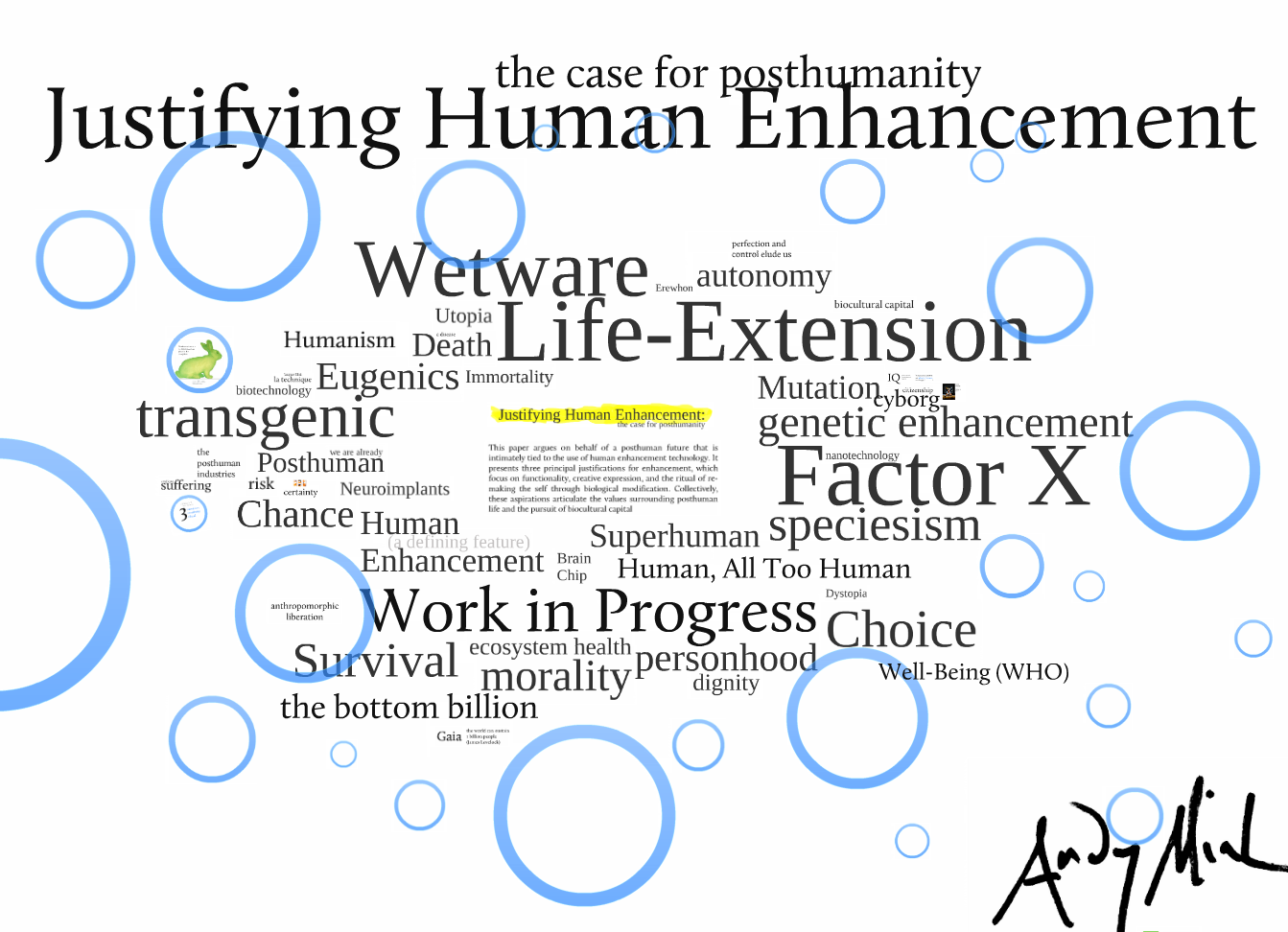

Justifying Human Enhancement: The Case for Posthumanity

Human Enhancement Technologies @ Swiss Re Centre for Global Dialogue

Doping & the Tour De France [VIDEO]

Social Media & Cities: Strategy

London 2012 Cultural Olympiad Social Media Evaluation (2013)

The 360 degree Olympic News Experience

!["I, Scientist" at TEDx Warwick [VIDEO]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/563face7e4b06c325c739ba9/1447019575958-NVZOYLTVWZ2QEWH1TPEM/image-asset.png)

"I, Scientist" at TEDx Warwick [VIDEO]

Can Twitter open up a new space for learning, teaching and thinking?

Justifying Human Enhancement: The Accumulation of Biocultural Capital (2013)

Google Glass Envy

Social Learning 2.0: A New Teaching Ethos for Universities

Oscar Pistorius granted bail