Make it stand out

What’s been happening?

Why the doping problem is here to stay

Why Wasn't Lance Armstrong Caught Earlier?

De Morgen publishes my Lance Armstrong piece

My take on Lance Armstrong in Wired Magazine

TEDx Warwick

My secret article on Lance Armstrong

So Long, Lance. Next, 21st-Century Doping.

The A to Z of Social Media for Academia

It's not the end of the world, yet

#LoveHE + Love Social Media?

To Tweet, or Not to Tweet?

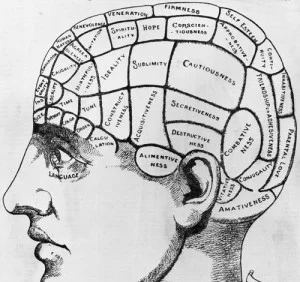

Mind control over robotic arms

Neohumanitas #bioethics

my new web project #REF2014 for Unit 36

Can technology set you free?

The War on Doping

Democratic Art

The Olympic Games and Creative Activism

Watching the Hashtags