Make it stand out

What’s been happening?

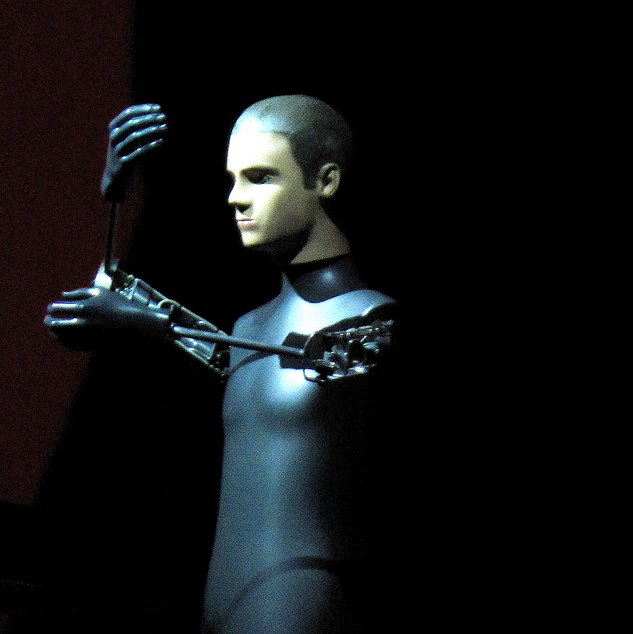

You have been upgraded

GATTACA 20 years later

Biodesign in the Antropocene

LIFE 2.0 Future Everything #Futr16

How to make your own superhero

Congress of Brilliant Minds

![Doping & Cycling: Scrutinising the most superhuman sport [VIDEO]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/563face7e4b06c325c739ba9/1447019579383-EYUHAWVC4BZHDCJOTIKZ/image-asset.png)

Doping & Cycling: Scrutinising the most superhuman sport [VIDEO]

Human Enhancement Technologies: Pushing the Boundaries (2013)

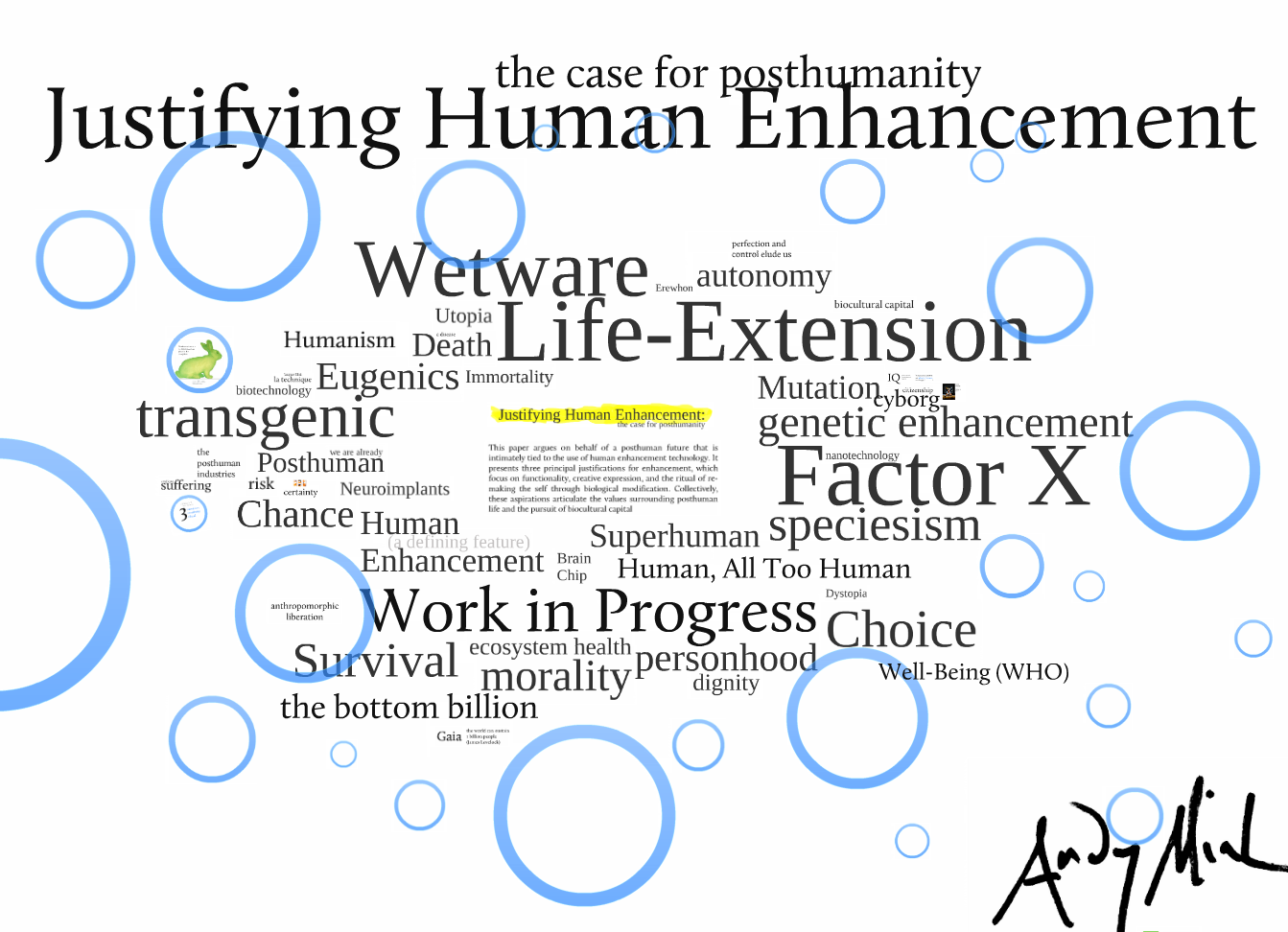

Justifying Human Enhancement: The Case for Posthumanity

Human Enhancement Technologies @ Swiss Re Centre for Global Dialogue

Justifying Human Enhancement: The Accumulation of Biocultural Capital (2013)