Make it stand out

What’s been happening?

Putting the NHS in Fortnite

Re-Thinking Journalism

Protecting the future of News Media

Why academics should care about social media

The A-Z of Social Media for Academia - Re-launch

Academia 2.0

Social Media for Academics

IOC #athletesforum

Should you get a smart watch? #MobTechEdu

Social Media and the PhD @LSENews

Social Media for Research Impact

The future of universities

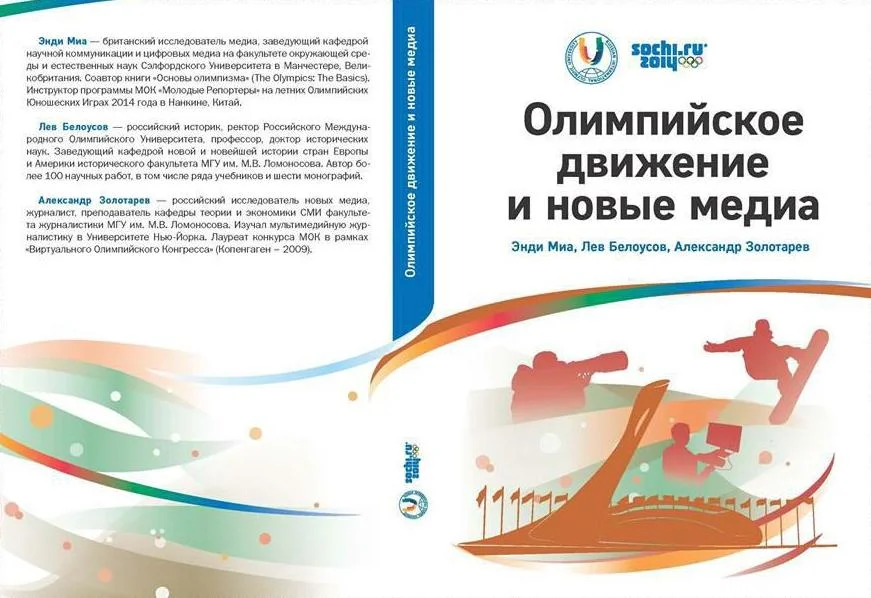

The Olympic Movement and New Media (2014)

Smart Cities, Smart Sports

Social Media & Radio: A Natural Born Partnership?

Sport, Technology, & Social Media

![Sport Accord Convention: Youth Club [VIDEO]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/563face7e4b06c325c739ba9/1447019583292-PF7N0370UKIF8K8W31C8/image-asset.jpeg)

Sport Accord Convention: Youth Club [VIDEO]

Social Media & Academic Life [VIDEO]

![Everything Everywhere: An Academic's Life on Social Media [VIDEO]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/563face7e4b06c325c739ba9/1447019580286-DITKBKRWZ7J8ZG15HCL0/image-asset.png)

Everything Everywhere: An Academic's Life on Social Media [VIDEO]