Make it stand out

What’s been happening?

New Scientist Live - October

Differently Abled Takes the Spotlight #Paris2024

Athlete 365

Sport 2.0 @ #MeCCSA2018

Sarajevo 1984, 33 years later

The Photographers of Rio 206

Sport's Digital Revolution

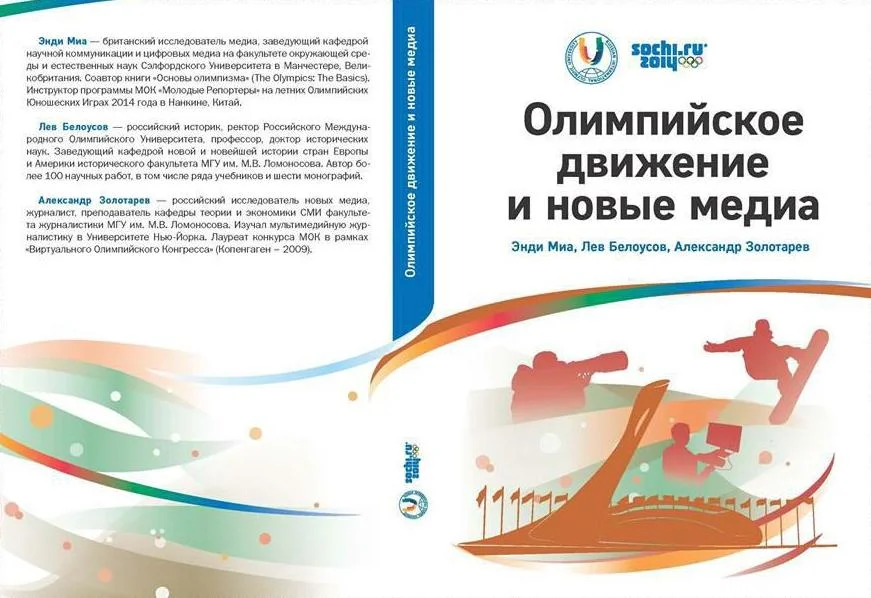

The Olympic Movement and New Media (2014)

Being Gay at the Sochi 2014 Olympic Games (2014)

London 2012 Cultural Olympiad Social Media Evaluation (2013)

The Olympic Games and Creative Activism

Watching the Hashtags

From London 2012 to Rio 2016 #Olympics

Are the Olympic Games Good for humanity?

Future Sport

Emoto 2012