Make it stand out

What’s been happening?

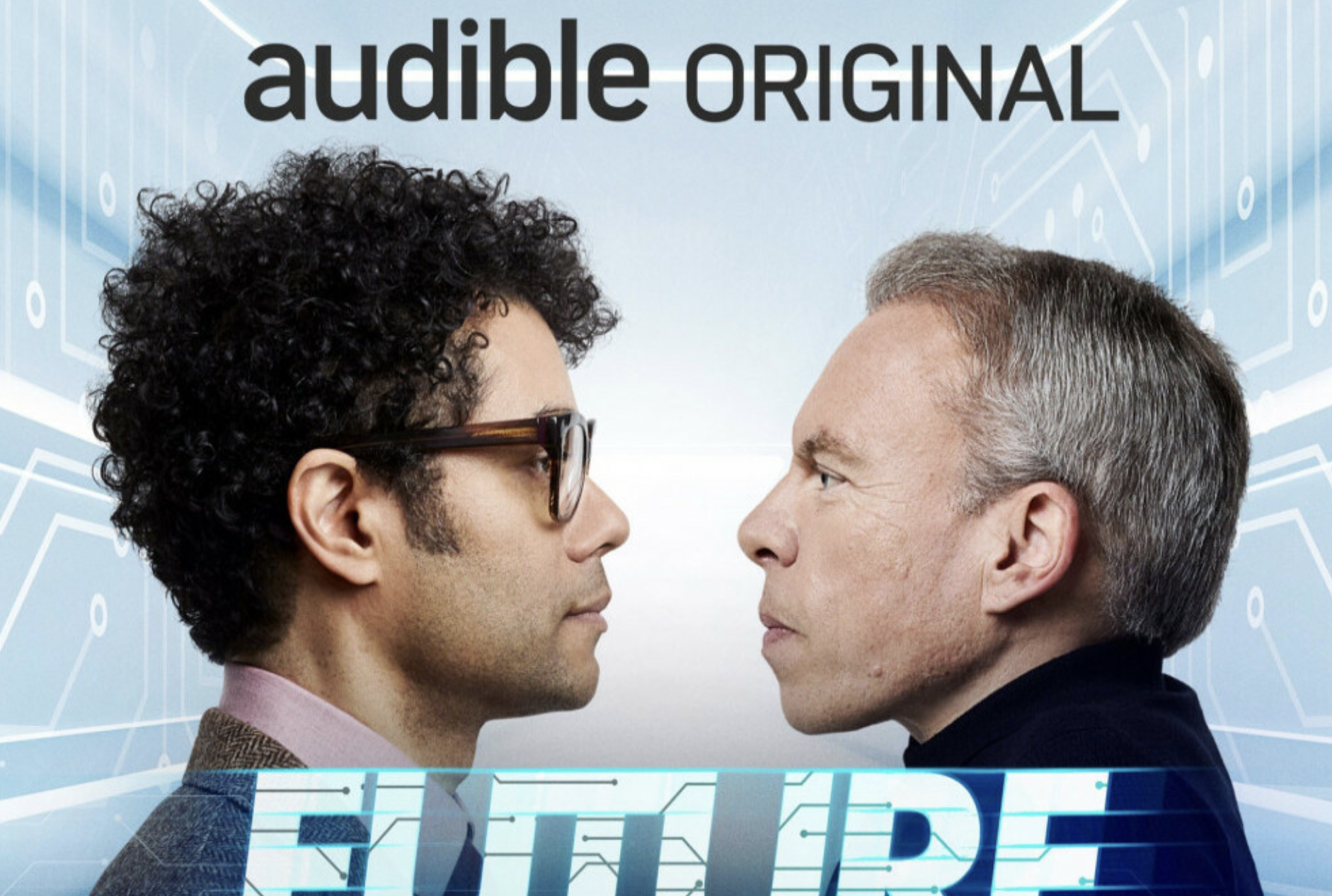

Future Tense on Audible

Artificial Intelligence is now translating fiction

REVIEW: Grand Theft Hamlet

Me and My Digital Twin

Differently Abled Takes the Spotlight #Paris2024

What's next for the Olympic Games?

Should schools ban mobile phones?

REVIEW: What Oppenheimer teaches us about science

Fast Forward podcast

The Future isn't STEM

What Clubhouse tells us about the future of social media

The Hyperquantified Athlete

Man 2.0

Esports and AI

The most important, least important thing

Digital homeschooling: we need to rethink our worries about children’s screen time

Can Virtual Reality Help Sports Fans Experience Game Day In A Post COVID-19 World?

‘How Our Drone Society was Made by Artists and What it Tells us About Ourselves’

Don’t give up on your non-virus-related research