Make it stand out

What’s been happening?

Multiplicity (1996)

I, Robot (2004)

The Cider House Rules (1999)

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004)

Mar Adentro (2004)

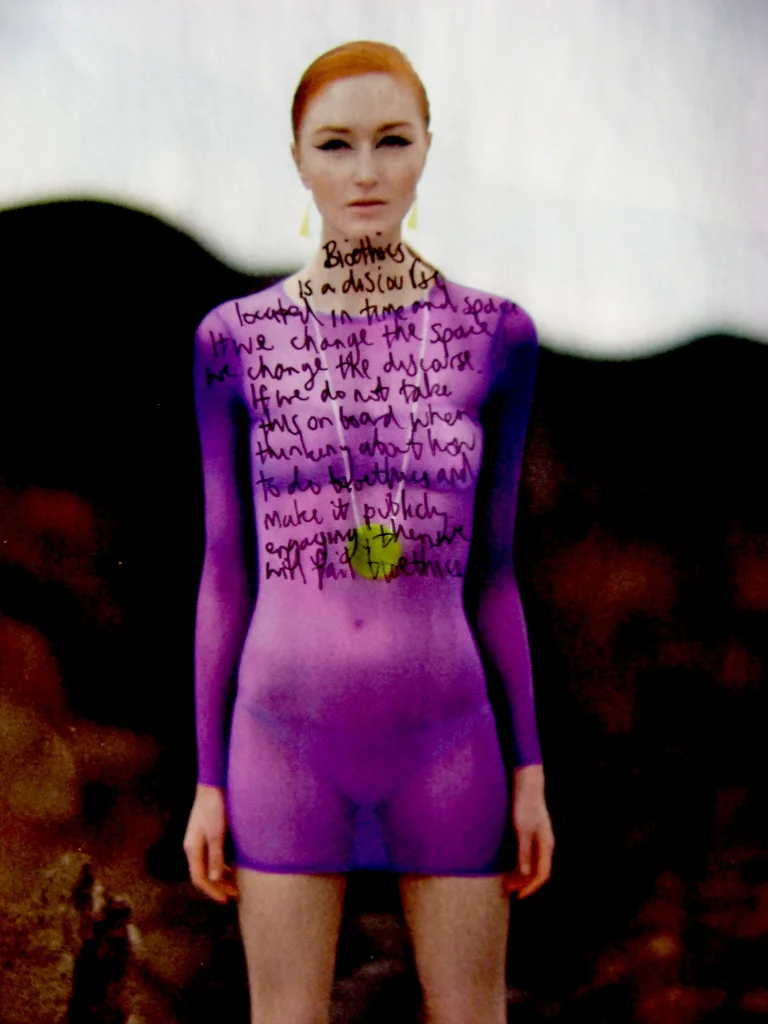

uh oh, another site: Bioethics Port

Stelarc - The Body is Obsolete - Contemporary Arts Media (2007)

Human cloning: why is there a fuss? (Lee Silver) (2006.09.21)

Transhuman minds? Is cognitive enhancement a human right? (London, 11 March, 2008)

Olivier Goulet

LESS REMOTE: The Futures of Space Exploration: an Arts & Humanities Symposium

SciBarCamp (Tornoto, March 15-16, 2008)

Inside the mind of a marathon runner (2008)

Engineering Greater Resilience or Radical Transhuman Enhancement (2008)

A Deep Blue Grasshopper: Playing Games with Artificial Intelligence (2008)

Ethical Considerations of Human Performance Optimisation (2008)